Swakelola Tipe III has the potential to create sustainable collaboration between the government and community organizations or CSOs in the procurement of goods and services. However, currently there are still a number of challenges in applying this scheme. For this reason, massive education and outreach regarding Swakelola Tipe III are very much needed.

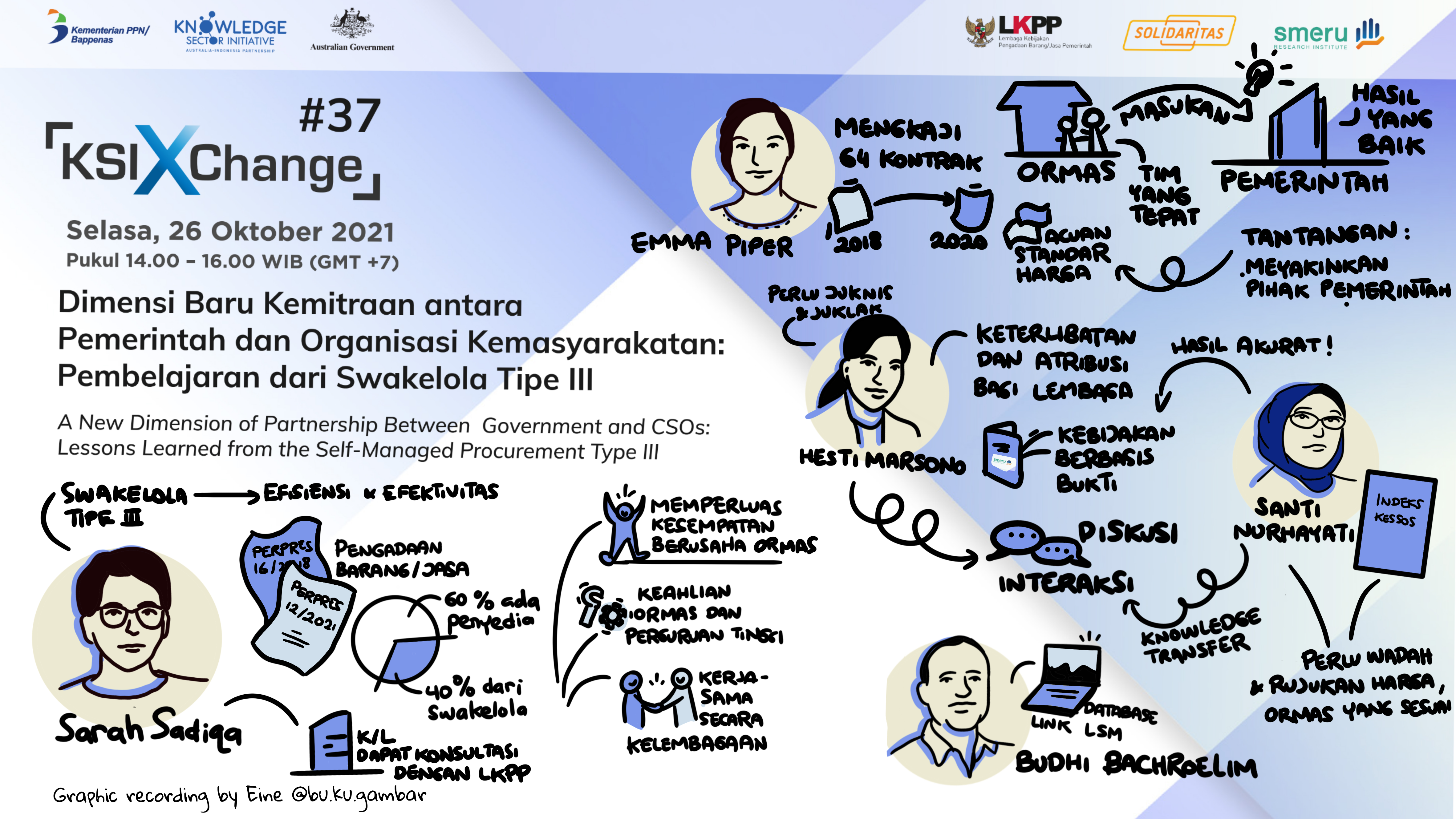

That was the message that amplified in the online discussion entitled "Learning on Government and Mass Organization Cooperation Using Swakelola Tipe III 2018-2021" on Tuesday (26/10/2021). This discussion was organized by Knowledge Sector Initiative (KSI) with the National Public Procurement Agency (LKPP). In this discussion, four resource persons were present, namely Acting Head of LKPP Sarah Sadiqa, Emma Piper as SOLIDARITAS representative, Director of Operations and Finance of The SMERU Institute Hesti Marsono, as well as goods and service procurement practitioner Santi Nurhayati.

Swakelola Tipe III is one of the schemes in which government goods/services are procured which has been enacted in Presidential Regulation (Perpres) Number 16 of 2018 concerning Public Procurement of Goods/Services which was later updated in Presidential Regulation Number 12 of 2021. This procurement method allows the government to access the unique expertise of CSOs to meet the needs of public goods/services with financing from the national budget, APBN or the regional one, APBD. In the previous procurement regulations, there was no mechanism that would allow the involvement of non-governmental research institutions and non-profit community organizations in such processes.

According to Hesti, before SMERU Institute used Swakelola Tipe III, usually any cooperation with the government would use Swakelola Tipe I which was considered less than ideal. This is because representatives of CSOs can only be contracted on behalf of individuals, not on behalf of institutions. Thus, the cooperation cannot be used to build the institutional portfolio. "However, since using Swakelola Tipe III in 2018, collaboration between CSOs and the government is more sustainable because it is no longer on behalf of individuals, but takes place institutionally," she said.

In addition, Hesti continued, this Swakelola Tipe III provides space for CSOs to be involved in formulating policies or planning, together with the government. This scheme allows the transfer of knowledge and skills between the two parties. This mechanism is also said to be able to provide alternative funding for CSOs and develop a portfolio of involved organizations.

Emma articulated the same thing. In a study conducted by SOLIDARITAS on the use of Swakelola Tipe III since 2018, it was found that this mechanism formalizes a mutually beneficial relationship between CSOs and the government. Prior to 2018, such collaboration usually required the involvement of third parties, such as donor agencies. This strategy is necessary because there is no procurement mechanism that allows direct cooperation between the government and CSOs. Hence, donor agencies contract with CSOs to carry out a job, such as a study or research, that is required by the government.

“In Swakelola Tipe III, the government is more appreciative of the expertise and capabilities of CSOs. Usually, when making a new policy or a new program, the government needs to understand what the people's needs are. It is not easy for the government to understand thisdue to the limited time and resources, including limited access to reach out to the community, especially to marginalized groups. This is where CSOs can play a role in supporting and increasing government capacity,” said Emma.

Meanwhile, according to Santi, Swakelola Tipe III has advantages in terms of ease of process. In addition to a simpler process, her organization has come to understand that if public procurement processes are supported by those with the right expertise, the work goes can be completed quickly. CSOs have expertise or skills that other institutions, including government agencies, are not equipped with.

Opportunities and challenges

Swakelola Tipe III, according to Sarah, provides greater business opportunities for CSOs. In addition, Swakelola Tipe IIIcan promote innovation in the field of research. If previously Swakelola was only known among the government's internal circles, now the government needs to reach a wider circle, including CSOs and private universities. This dynamic is the background for the revision of Presidential Regulation No. 16/2018 concerning Government Procurement of Goods/Services to become Presidential Regulation No. 12/2021.

"For the 2021 budget, our APBN is around Rp. 2,000 trillion. Of this amount, half or around Rp 1,000 trillion is processed through the procurement of goods and services. If it is dissected again, about 60 percent is carried out with the provider (private sector) and 40 percent is carried out through Swakelola. We can therefore see how important Swakelola is as part of the process of public procurement,” said Sarah.

Sarah added that the types of activities that are mostly carried out in Swakelola Tipe III are research or preparation of studies, education, activities related to community empowerment, mentoring activities, and information technology development. Until October 2021, the amount of money for conducting public procurement through Swakelola Tipe IIIwill reach around Rp. 2 trillion, for a total number of 3,300 procurement projects. Compared to 2020 data, the amount was around Rp. 1.3 trillion for a total of 4,900 procurement projects.

Despite producing a number of positive impacts, based on Solidarity's study, there are still a number of challenges in implementing Swakelola Tipe III. Among these challenges is the fact that there are still many parties who do not understand the mechanism of Swakelola Tipe III. There are still doubts about what can and can't be done.

“Another challenge is around the budget and payments. In preparing a budget proposal, sometimes there is confusion regarding which cost standards should be refered to for Swakelola Tipe III,” said Emma.

In order to make the details of Swakelola Tipe III accessible to the public, Hesti encouraged the government to organize a learning forum, where parties with experience in using Swakelola Tipe III could share their experiences. Another recommendation is to strengthen coordination and facilitate more trainings within ministry units, agencies and local governments so that understanding regarding Swakelola Tipe III could be more standardized.

“Lastly, we see the need for guidelines in the form of technical guidelines or implementation instructions for Swakelola Tipe III. We hope that this additional information will not make this scheme rigid, but will instead provide more comprehensive guidelines,” said Hesti.

KSIxChange is an interactive discussion initiated by KSI, a partnership between the governments of Indonesia and Australia with funding from the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT). KSIxChange which is held at least once a month aims to support the implementation of government programs through increasing public discourse based on the use of evidence in the policy-making process. (*)