The COVID-19 pandemic, which drove digitalisation in various aspects of life, has further widened the economic gap, and it takes more than economic incentives to support affected groups.

This theory was presented by an economic researcher from the University of Indonesia, Teguh Dartanto, at the KSIxChange#36: ALMI Special Scientist Series, on Tuesday 21 September. The forum, ‘How Social and Humanities Science Can Protect Vulnerable Groups from the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic’, was held by the Knowledge Sector Initiative (KSI), in collaboration with the Indonesian Young Academy of Science (ALMI).

Speakers presented the situation of vulnerable groups in Indonesia. Other speakers included an arts and culture researcher from the State University of Jakarta (Universitas Negeri Jakarta), Aprina Murwanti, an education researcher from the State University of Semarang (Universitas Negeri Semarang), Zulfa Sakhiyya, the Executive Director of Sajogyo Institute, Maksum Syam, a social, cultural and religious science researcher from the National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), Najib Burhani, and a health researcher from Hasannudin University (Universitas Hasannudin), Sudirman Nasir. Inaya Rakhmani and Evi Eliyanah from ALMI moderated the discussion. This event was broadcast on The Conversation Indonesia’s YouTube channel and was equipped with English and Bahasa Indonesia interpreters, as well as sign language interpreters.

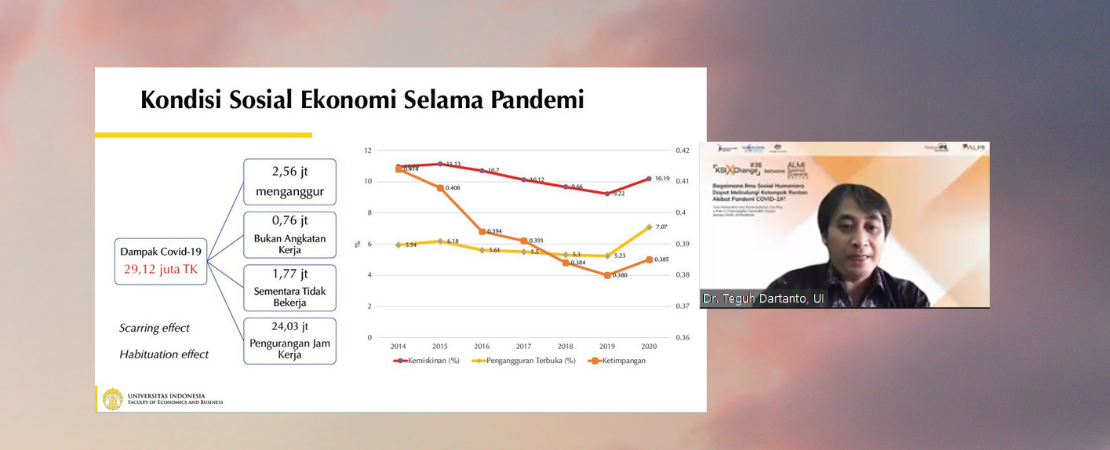

Teguh’s analysis of the gap during the pandemic was based on a digital divide perspective. [ZA(1] He argued that unequal digital infrastructure and literacy contributed to widening the gap between the rich and the poor. “This occurred due to the inevitable economic disruption caused by the digitalisation process,” Teguh explained.

Not all jobs can be done online. Teguh said that the ‘average worker’ in the lower-middle income bracket must work on site. “When the government limited people’s activities, they practically did not receive any money,” Teguh said.

This is inversely proportional to the situation of workers’ groups in the upper-middle income bracket. These groups still received and could even increase their income. “The nature of their jobs enabled them to earn income through the internet. Of course, expenses that were normally incurred for transportation and so on decreased, not to mention if some companies supported their employees to work from home by providing incentives,” explained Teguh.

According to Teguh, this situation made the gap even wider. This was evidenced, for example, in news stories that reported survey results showing that the wealth of public officials during the pandemic had actually increased.

Despite being called a crisis, the context of the COVID-19 pandemic is significantly different from previous crises. During the financial crisis in 1998, for example, it was the upper-middle class who were directly affected. “At the time, poverty increased, but the inequality rate decreased,” said Teguh.

More than incentives

Teguh said that to alleviate the current situation of the [ZA(2] lower-middle income groups would be “no walk in the park”. It needed more than just incentives.

From the digital divide perspective, the solution is not just evenly establishing internet infrastructure. Because even though the infrastructure is evenly in place, individual access to gadgets and the internet is a different issue. “Even if everything has been set in place, the next question is what the access is used for. Can we be sure that people are indeed accessing knowledge from the internet that can improve their opportunity and means of livelihood[ZA(3] ?” Teguh asked.

Regardless of this complexity, Teguh appreciated government efforts to protect vulnerable groups affected by the pandemic, especially lower-middle income groups. However, this appreciation was not without caveats.

Teguh argued that basic government data did not describe the actual impact of the pandemic on the people. “This is why on-demand programs are important, because the pandemic has made classes in the community so fluid. People who had been working for a long time have suddenly lost their jobs,” said Teguh.

In his opinion, policymaking often only uses an economic point of view, when in fact the social-humanity approach plays an important role in mapping vulnerable groups that have not received economic assistance more effectively. Implementing a social-humanity approach can also help the government design inclusive and adaptive social protection policies to respond to changes.

Teguh highlighted the long-term impact of the pandemic on human resource quality, including potential future learning losses, which will ultimately affect the poverty rate. “The online education process, which cannot be engaged by every child in Indonesia, has the potential to be a problem in the future,” Teguh said. “The output of students using online learning will surely be different (than face-to-face education)."