Over the last several decades, there has been a shift to applying knowledge systems as solutions in the government policy making space. The long term goal of the KSI project is to highlight what a knowledge system that drives transformational change looks like. I had the privilege, along with co-authors Derick W. Brinkerhoff, Robin Bush, and Petrarca Karetji, to research, think and reflect on these issues. Please see the following “virtual interview” of our dynamic research team.

The Importance of Knowledge Systems & Evidence Based Policy

What was the catalyst for writing this policy brief? What do you hope people take away from it?

Jana C. Hertz: “At the time of writing this policy brief I was director of RTI’s innovation led economic growth cross-Institute team promoting innovation ecosystem development globally. I was interested in the intersections between innovation ecosystems and knowledge ecosystems, the former focused more on science and technology leading to research commercialization and the latter on social impact through public policy. In conducting the literature review we found there was an imbalance of research related to innovation versus knowledge ecosystems with comparatively fewer citations related to knowledge ecosystems.

In the RTI managed Knowledge Sector Initiative in Indonesia, which I currently lead, we have found that in the Government of Indonesia’s drive to promote innovation there is a need to balance this drive with the social impact of science and technology applications. For example, in the Covid-19 response in Indonesia (and internationally) there is a need to balance the drive for a vaccine, production of PPE, and new treatments with research on the socio-economic impacts of Covid-19 and impact on people’s livelihoods. One core insight from this policy brief, in my opinion, is to invest in the knowledge system components as well as the interaction between components. There is a need for a “whole of government” as well as “whole of society” response to global challenges including Covid-19. There couldn’t be a more urgent time to promote evidence-based policy through robust knowledge systems.”

New Literature and Increasing the Visibility of Knowledge Systems

Why are knowledge systems underrepresented in the literature in comparison to innovation systems? How does this policy brief contribute to the literature?

Derick W. Brinkerhoff: “The early literature on evidence-based policy looked at the person-to-person relationship between researchers and policymakers and focused on the dynamics that affect how and whether what researchers produce respond to the needs and desires of policymakers as research consumers. This supply and demand relationship was examined to some extent in a vacuum with a concentration on the personal characteristics of the suppliers and consumers. The introduction of a systems perspective led analysts to look to the contextual factors that affected this relationship, which in the literature has evolved into the current focus on knowledge systems.

Literature on innovation ecosystems to some extent overlaps with work on knowledge systems and can introduce confusion. A key distinction in innovation ecosystems is the emphasis on how system actors combine technical, commercial, and financial resources to bring new products to market. In contrast, the categories of knowledge that knowledge systems generate are not limited to market innovations (though they may contribute) but include—as this brief details—policy-relevant studies that inform government decisions.

This policy brief fleshes out the elements that comprise a knowledge system and then offers a concrete example from Indonesia of how a systems-sensitive perspective led to progress in helping Indonesian government policymakers to interact with local policy research institutes to craft better policy solutions to key problems facing the country. “

Applying Knowledge System Learning

What was one of the most important lessons learned from supporting knowledge system development in Indonesia?

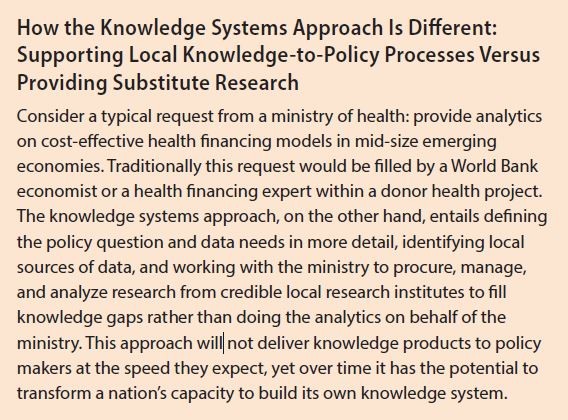

Robin Bush: “One of the most important things we learned was that taking a systems approach is radically different, in fact counter-intuitive to, the approach usually taken by traditional development projects that aspire to improve policy. Traditionally, a policymaker has a data or analytics need, the development project fills it, box ticked. But with a systems approach, the policymaker is encouraged to go through a process of identifying the real evidence gap, making sure there is a diversity of voices weighing in on the issue, and then procuring, producing, and using the knowledge product through government systems -- that is a much longer, more complicated process. And we learned that in the beginning, when both donors and policymakers are not used to this process, there can be a lot of resistance. It takes some time to get all stakeholders on board in supporting the value of taking that longer path. But, once you have a critical mass of key decision-makers on the same page, transformational change is possible.”

Including a Diverse Perspective

The recommendations in the brief talk about the importance of promoting a diversity of voices within the knowledge system and promoting collaboration among parts of the knowledge system. In your experience, how is this best accomplished?

Petrarca Karetji: “Well, if you think of knowledge systems as ecosystems, you can then recognize how different institutions and individuals interact as living organisms. You can also see that the interactions are not always systematic, or in accordance to set parameters and relationships. Diversity of voices allows for increased interaction from all elements within the ecosystem, supporting discovery or innovation. However, the less diversity there is, the less effective the knowledge “system” is in adapting to its environment and in adopting new perspectives. This is particularly important if the result we are looking for, particularly when we are talking about addressing multifaceted, complex development issues, is improved collaboration between institutions and individuals.

Suppressing voice or the dominance of one voice or perspective over the others creates an artificial rather than a natural and mutually beneficial process of collaboration. Such collaborations are difficult to sustain in the long run, particularly without incentives or coercion, and there are no incentives for those “forced” into the relationship to go beyond a minimum effort. We saw this in the various working-groups supported by KSI, and in other efforts I have observed in the past. The most effective working groups able to progress agendas effectively, are always working groups where representatives felt able to express themselves and contribute, and so results achieved were seen as joint accomplishments. This creates positive dynamics leading to increasingly ambitious agendas.”

What’s Next

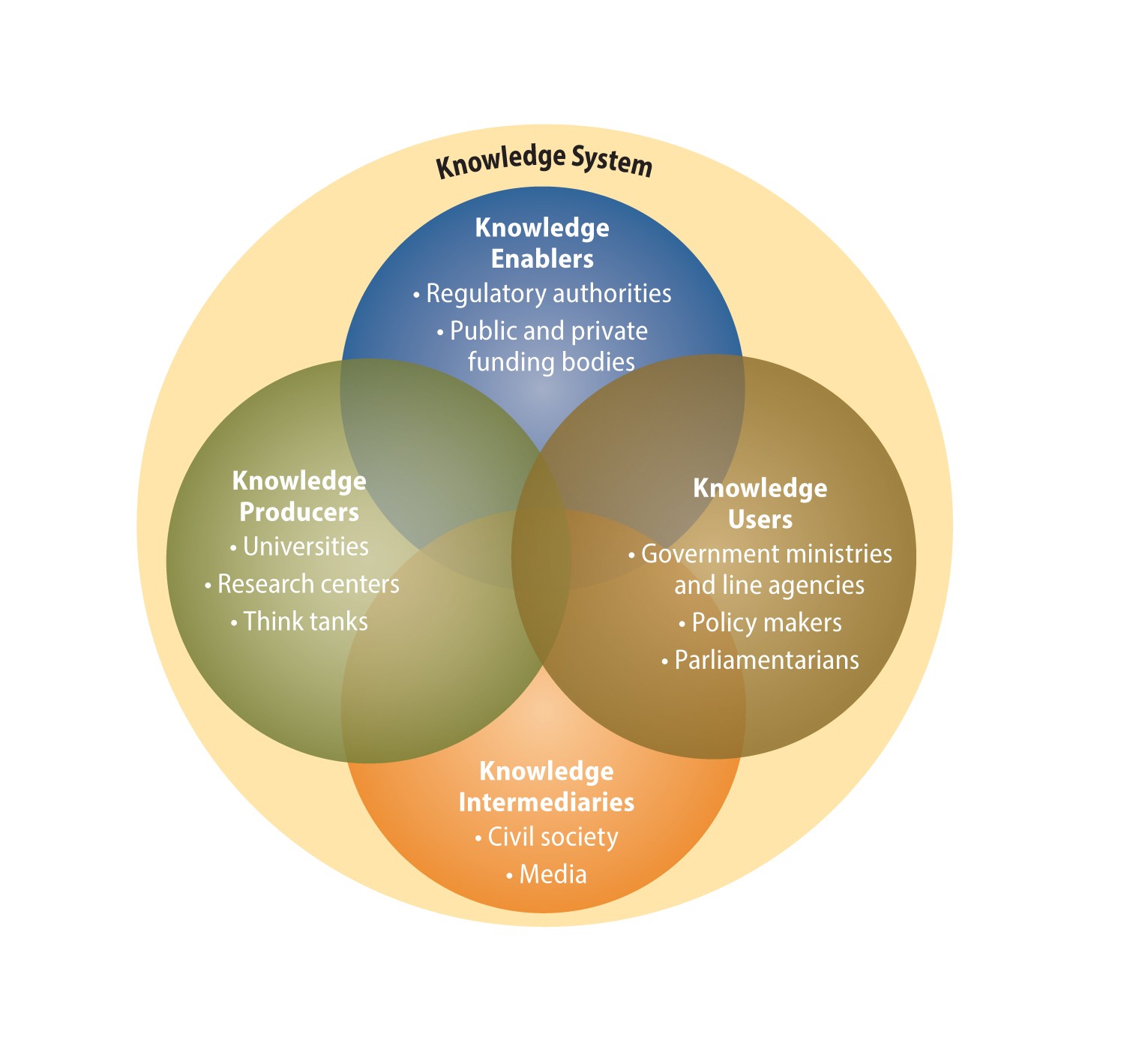

Applying the model to experience with the Knowledge Sector Initiative (KSI) in Indonesia, we demonstrate how a systems perspective helped policymakers interact with knowledge producers, enablers, and intermediaries to tailor policy solutions to key problems facing the country. I encourage you to read the brief to delve into the rich details of the model, KSI experience, and our recommendations for more effective knowledge systems. My co-authors and I welcome your feedback on the model and are eager to hear about your experiences. Knowledge Systems: Evidence to Policy Concepts in Practice