KSI Interview with Lies Marcoes: GESI Perspective in Research for Development

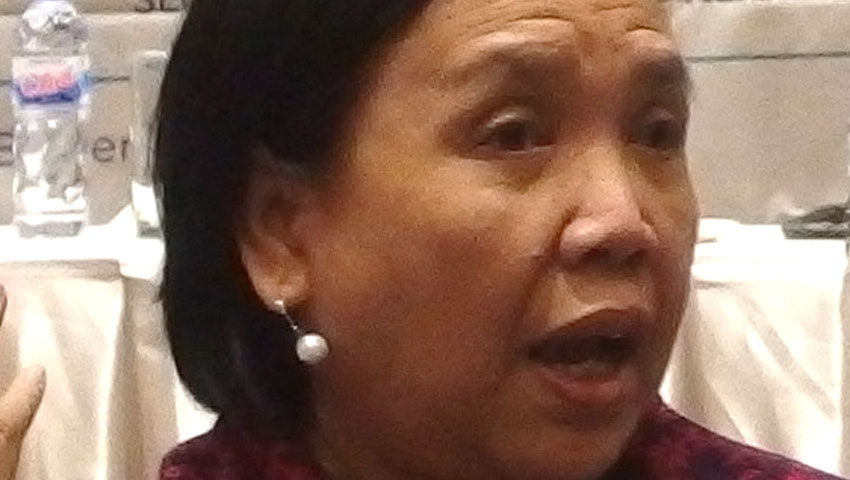

Lies Marcoes Natsir is one of Indonesia’s foremost experts in Islam and gender. She has played a pioneering role in the Indonesian gender equality movement by bridging the divide between Muslim and secular feminists and encouraging feminists to work within Islam to promote gender equality. Lies is a passionate and talented trainer – frequently used by KSI and other DFAT programs – and has used these skills to change people’s attitudes to the status of women in Islam. With her strong leadership and commitment, Lies has empowered countless Indonesian women and brought gender into mainstream parlance in Indonesia.

Q: Can you tell me a little bit about your background?

A: I graduated from IAIN/UIN Jakarta, from the Islamic Theology Faculty, with a Religious Comparison Major. After more than 15 years as an activist in the reproductive health area, including as a program manager at the Association of Islamic School Development and Community (P3M), I received a scholarship from the Ford Foundation for my Masters program in the field of Health Anthropology at the University of Amsterdam.

I have also been a researcher and activist in the women’s movement in Indonesia. These are two roles that, in a number of cases, are not always linked to each other and not always played by one person. Usually, people choose to become activists by using the research outcomes of another institution as the basis for their cause, or they only become a researcher without advocating their research outcomes.

I may be a bit unique, in that I do both. I love the research world, especially research on religious social anthropology. This issue gave my life colour and meaning. I love to go to the field; finding out, asking questions, listening to stories, and writing them up with a specific discipline and theory, particularly feminism. By doing this, I can explain a phenomenon by using a critical perspective related to the relationship (authority) between men and women, a perspective that can dismantle gender prejudice and bias, and the resulting discrimination.

I also love to write. I love writing research outcomes. I often write an extract of my research outcome in the opinion section in media such as Kompas, the Jakarta Post, or on social media by using popular and easy to understand language. When I am writing all of these, I feel that I am conducting advocacy to change perspectives or policies.

In the context of time, I think my momentum was timely, even though any time can be used as momentum for anyone to experience changes in their lives. I was going through life in the era of mid-New Order, which at the time was very arrogant towards people.

The political engine of the New Order, namely the Golkar party and civil servants, became the most effective backbone in supporting the regime. Meanwhile, others of us, NGOs, the student movement and the press, must work under a shadowy pressure – invincible but frightening. Speaking on women’s rights at the time, we had to point out the mistakes of the Family Planning (FP) program for example, a program that has been proven to support development by significantly reducing the birth rate. We had to explain that a program, even with its positive impact, must still be questioned if, in its implementation, it takes away individual basic rights of women controlling their own bodies and violates the principles of democracy by forcing their will without any room for negotiation. We know that at the time, FP was done coercively, using military means, systemic threats, using the approach of shame for those who did not follow the State’s will, and did not leave room to question or refuse the program. These methods, according to us activists, violated the basic principles of freedom and jeopardized the program itself. People were following FP because of force, not because of their own awareness, but through mobilisation. Now, we can see the result, we have found the evidence that FB has been rejected for reasons that should have been discussed in the past–reasons related to its objectives, benefits, methods and origins. And this comes from a domain that should have been discussed first, such as religious or demographic political perspectives.

I used to speak about reproductive health in the face of state coercion, now my research and advocacy remains on reproductive health issues. The difference is that we used to face the coercive force of the State, now we are facing another shadowy force from the religious perspective, which also feels entitled to have power and control over a woman’s body.

Q: Can you explain how feminism is made operational in your research?

A: In researching any theme, I always want to critically observe the power relationship, including the gender power relationship.

With this gender analysis and feminism, I can also see the agency of women: how they provide meaning, either by being compliant or fighting against the patriarchal will that is making them suffer, but it requires a critical awareness to realise this. For example, when I researched the radical movements in Indonesia, I read several research outcomes on this issue. I am baffled as to how a religious movement in Indonesia can ignore the involvement of women. How can something so real and visible manage to be skipped in the research framework. For example, the wanted terrorist Noordin M. Top can survive because he is camouflaged by forming a regular and normal family. Don’t we want to know who the wife is, whether she is afraid or not, how did they know each other, what is the wife’s view of her husband’s cause? In short, don’t we want to know how the terrorist moves from one city to another, who washes his underwear? I am very surprised that research on a religious movement in Indonesia can fail to question the women’s position. At that point, I assume there is a huge gender bias. Terrorism is considered a masculine world, the world of men. But this bias is lost in the research.

Based on this curiosity, I designed research on women and fundamentalism. I tried to observe it in a round way, not directly at the heart of the research on radicalism. I agree with the opinion of Ihsan Ali Fauzie from PUSAD Paramadina, who concluded that fundamentalism is a way to radicalism. Together with a researcher of Yayasan Rumah Kita Bersama (Rumah KitaB), we intensively interviewed 20 women on what can connect women to a fundamentalist point of view and movement in Indonesia. The outcome was very interesting. In each woman we interviewed, there is an agency to fight and engage in a jihad to defend her religion. The women attached a very personal meaning to jihad. Of course, this concept was received through their involvement in their fundamentalist group. Here, there is an agency role of women, namely as ‘servants’, both in providing meaning or even criticising the organisation or their fundamentalist group.

A more interesting thing is how women attach meaning to their jihad. Fundamentalist groups place jihad in two categories. One is major jihad (jihad kabir), namely jihad that puts your life on the line in the battlefield/conflict area. Meanwhile, small jihad (jihad saghir) is a jihad related to the role of women to give birth, especially to boys, that will become the actors of major jihad, and being patient while their husbands go on jihad. However, women from younger generations are not satisfied by this social role. They negotiate to participate in major jihad, for example by becoming bomb carriers. This is an interesting fact. But it is the researcher’s job to question this fact in a deeper way.

In my research, because I used gender analysis and feminism, I raised the question of why women feel dissatisfied with their traditional roles in performing small jihads. This question brought me to a more interesting finding. It would seem that the social position of women within fundamentalist groups is very low. They are unappreciated, unseen and unrecognised as something that provides meaning to jihad. These young women are desperate to prove their bravery, even being braver than men. They want their role to be seen and recognised. The only way to prove this is by sacrificing their lives (as the bomb carrier). In the theological concept, actors of jihad are incentivised by receiving angels in the next world, but what is in it for the women? The concept is not as bright and clear as for men. Despite this, women still want to prove that they are willing to put their lives at risk. With this, they are ‘respected’ and their presence and existence are accepted. We can then understand why some women are willing to blow themselves up by carrying a bomb and thinking of this as a jihad (read the publication of Rumah KitaB entitled the Testimony of Servants: A Study about Women and Fundamentalism in Indonesia, red.).

Q: Violence against women is a long-standing phenomenon. How does your research bring to light data and information on the facts of violence, and thus, become evidence for policy change and social justice?

A: This is an interesting question. This explains my two working arenas – research, and writing for advocacy. I wrote an article in Kompas to respond to the statement of the Minister of Education and Culture, Mohammad Nuh, (he was in power from 22 October 2009 to 27 October 2014, red). At the time there was a rape of a Junior High School student in Depok, committed by her senior. The school refused the victim’s right to go to school after the rape. The minister said that this was not sexual violence, but consensual sex. So, instead of finding a solution on the discriminatory action of the school, the minister condoned it in the name of protecting more students.

In this article, I explained that sexual violence against teenagers is similar to violence in dating. The point is rape can occur in a relationship initially built on a consensual basis, but at one point there is a coercion using the power relationship in the name of love. There is a gender difference that must be understood on the perception of teen boys and girls on the expression of love, the power relationship, and the meaning of a sexual relationship. This difference needs correct understanding that is not biased and not based on male assumptions.

Another example is the research of Rumah KitaB that I am leading on child marriage (there are 14 research titles that can be viewed on https://rumahkitab.com/project-list/karya/). Attempting to step out of the focus that sees child marriage as a result of poverty, we tried to further explore the root of such poverty. Child marriage has become a phenomenon that can be found almost anywhere in Indonesia, both in rural and urban areas. Data shows that one in five Indonesian women were married when they were under age, and two thirds of these marriages ended in divorce. Indonesia is in the top ten countries with the highest child marriage rates in the world. We tried to observe the root of the poverty, namely the changing living space in rural areas as a result of change of land ownership and its conversion. When men and community figures lose their access to land, they become more picky in dealing with public moral problems, including their teenagers. They tend to be more conservative and at least let child marriage slide. By doing this, they show their power politics role and receive economic benefits by becoming a regulation broker. At the analysis level, this research demonstrated how child marriage is actually a form of violence by adults to children. To make matters even more frightening, this violence is agreed upon between adults. Not one adult is challenging it. They often state moral reasoning, in the best interests of the child, covering up shame or resolving immoral conduct. This is contradictory, because marriage of a child is clearly immoral. They drop out of school, stop expressing themselves, and stop playing, which are their rights.

Among the institutions that we observed in the context of this research, there were ‘vague’ institutions. There were neither formal nor informal institutions, but they were extraordinarily effective in promoting child marriage practices.

Q: How do you, along with other researchers, advocate a policy change that is not reactive and does not target the issue on this ‘vague power at work’?

A: We see that child marriage is promoted not only by formal institutions, but by other institutions accommodating this practice. Emergency door regulations, such as dispensation to get married when under age from the Religious Court after the Religious Office has refused because it violated the Marriage Law is one of the accommodative formal institutions. Or, people take advantage of informal institutions, where a community figure is involved in approving a child marriage by conducting an under-handed marriage, which is illegal from the State’s point of view, but legal from a religious stand point.

Between these two institutions, there is a very powerful situation encouraging child marriage practices, neither by formal nor informal institutions. We call it a ‘vague institution’, namely decisions taken by unknown figures. It may be the mother, father, relative, a big family or the community. The point is marriage is done to cover up shame and resolve the anxiety of adults surrounding the child. This is particularly true when the child is pregnant, or is considered to have disturbed the family stability by the way the child expresses his or her sexuality. They are considered flirtatious, unable to control themselves, and so forth. This shame has plenty of power, but its bearer is so vague. That is what we mean by vague power at work.

The research on child marriage that we conducted has produced new theories that still need to undergo some testing, for example, the phenomenon of social orphans, where the child does not have a father and mother as a place for them to seek protection and help. Their parents have lost their social roles as parents due to severe and systemic poverty.

Q: What kind of progressive maneuver would you like to create through your research to improve the gap in the power relationship between women and men in Indonesia?

A: Our research on FP (publication entitled Religious Perspective Map on Family Planning, red.), fundamentalism, women in radical movements, or child marriage basically shows how religious views and institutions can take a larger role in protecting women. We do this by contrasting text and reality when text is used blindly as a tool to justify or legitimise violence against women. We show facts on this violence and face it with the normative, ideal teachings brought by religion. If we believe religion is a blessing for all humanity, why are only some people enjoying it? If religion teaches us good things, why does it result in bad treatment of women? Certainly, it is not about the religion, but how people interpret it in a biased and incomplete way. In the niche between the fact of bad treatment suffered by women and the normative ideal value of religion, we have the opportunity to build an alignment to women. The feminism analysis knife to me is a way to grow critical thinking and methodology to build alignment, namely thinking and action to address oppression.

Q: What trend do you want to see in the next generation of researchers and analysts that want to promote policy change for social justice?

A: A while ago, I saw a documentary video of a poet, Agam Wispi, an Indonesian runaway poet staying in Amsterdam. He was a poet for the People’s Cultural Institution (Lekra) from Medan, North Sumatera in the late 1930s. He was the most influential Lekra poet during 1950-1960s, before joining the navy and being stuck abroad during the 1965 incident. According to the records of the Literature Encyclopaedia developed by the Ministry of Education and Culture, his poetry contained reform never seen before, such as language, expression and emotional word choices. I was very impressed with his work because it contained anger about the social situation that he considered to be unfair for the poor.

In the 1980s, he was invited to Jakarta and he met young poets and writers in Indonesia. He was very impressed with how active these youths were. According to him, their work was very creative and they were acting to fight the oppressive regime.

Inspired by this interview, I see that a critical young generation is the most important element in social change. Issues of environment, labour and specific issues on the oppression of women are mobilised by activists. They are not just conducting research, but also consistently and persistently taking action to move and resist a bad situation. The methods may be different than during my years. The actions today are done through fun methods, out of the standard organisational boxes, but they produce very good results. Social media and technology are clearly helping them, while back in my era cell phones did not even exist.

I see the use of social media as an advocacy tool being a trend that will develop in the future. Infographics, short videos and short movies will become inevitable smart choices in this digital era to advocate policies from research outcomes. This is the era of youth in a fast-paced global era.

However, there are two things that can pose a threat. The first is ethics. The truth of social media news is very hard to trace, from research methodology and knowledge management perspectives. How the research was conducted is not explained, all we get is the outcome. We really must uphold ethics, if not, there will be research outcomes that cannot be academically accounted for, making it no different from hoax news. If false information is used for advocacy material, that is truly frightening and clearly wrong.

The second issue, and I feel that this is a crisis, is organisation at the grass roots level. It is there that the real fight for humanity issues lies. Who do we want to defend? Surely the oppressed people. To find them and build their resistance to oppression in the social or gender structure, they need friends. Who is currently working at the village level to organise the people? Political parties do not go that low, instead we have religious communal groups. A number of villages are lucky to be selected for NGO work. Beyond that, we expect the awareness to come from the villagers themselves, who regretfully, have not learned to truly organise themselves for more than 40 or 50 years. Existing organisations are established by the State through agents (village officials). Village elites become small kings who are currently managing their own funds, such as the village fund allocation. In my observation, this is an important facility to conduct advocacy for change. However, the institutional and organisational aspects at the lower level are very fragile. Village discussions become a technocratic mechanism where the voice of the marginalised, including women, is rarely heard. I feel that the trend of change should come from there, but who is over there? Without any critical people, without organisations based on the essence of democracy and public space free from primordial interests, we will let democracy die from its most basic core: representation at the village level.

So if you ask me what do I want to see in the future, I want people’s education at the village level. Not only Qur’an recital. Not only about livelihoods. I want a community organisation growing at the community level, the village. It is not enough through organisations managed by the village or recital/religious groups, but a critical people’s organisation, where people are aware of their rights, within which are elements of marginalised villagers who have the same opportunity to voice their opinions. Efforts toward this have clearly been done, but again, who is over there? I left the village a while ago. I am only looking from afar and am powerless to raise the awareness of my own village people. This is ironic for many activists of social movement and the Gender Equality and Social Inclusion, red. (GESI) justice movement.

Q: Within the next five years, how do you see the ‘GESI perspective in research for development’ helping to create and support a wider and more robust knowledge sector in Indonesia?

A: At the knowledge production level, we have to be able to prove that without GESI, just like the examples I put forward from several researches above, the research outcomes are not only inaccurate, but also lost. Lost here means that the knowledge production cannot fulfil the expectation, which should be the basis of policies. When the research is wrong, how can the recommendations be right? At the communication level, we need creative ways, just as activists do through media, but they must be very GESI-sensitive. Not for the sake of GESI itself, but so that knowledge can really be effective and knowledge can be easily read by policy makers.

I feel that issues related to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) must be prioritised. There are 17 targets that need robust knowledge production. This will also help policy makers to budget and plan a policy. A simple example is how many contraceptives are needed in this country? We cannot simply give up to the drug industry producers. Knowledge production must be able to complement the State with correct data, so that the State can meet the reach of contraceptives, thus meeting the rights of women.

SGD targets need good databases. The GESI perspective is important to be brought forward, especially for data on targets that seem to be neutral on GESI, for example, the target to eradicate malnutrition and famine, or targets on water and sanitation. Without using GESI, the target to eradicate malnutrition, stunting, famine, or to make clean water available will not be achieved. There needs to be an understanding of how the power relationship works and influences access and control of nutrition and clean water. The power relationship can be based on ethnicity, race, physical condition, or geographical condition, within which there should be the reality of the gender and age relationship.

Topic : gender equity, islam, leadership